Flipping to Delaware: What Non-U.S. Founders Need to Know

Every startup begins somewhere, but not every startup begins where it ultimately needs to scale.

For founders who launch their companies outside the United States, the initial incorporation choice is often driven by speed, familiarity, and local regulatory ease. That decision frequently gets revisited once U.S. venture capital enters the picture.

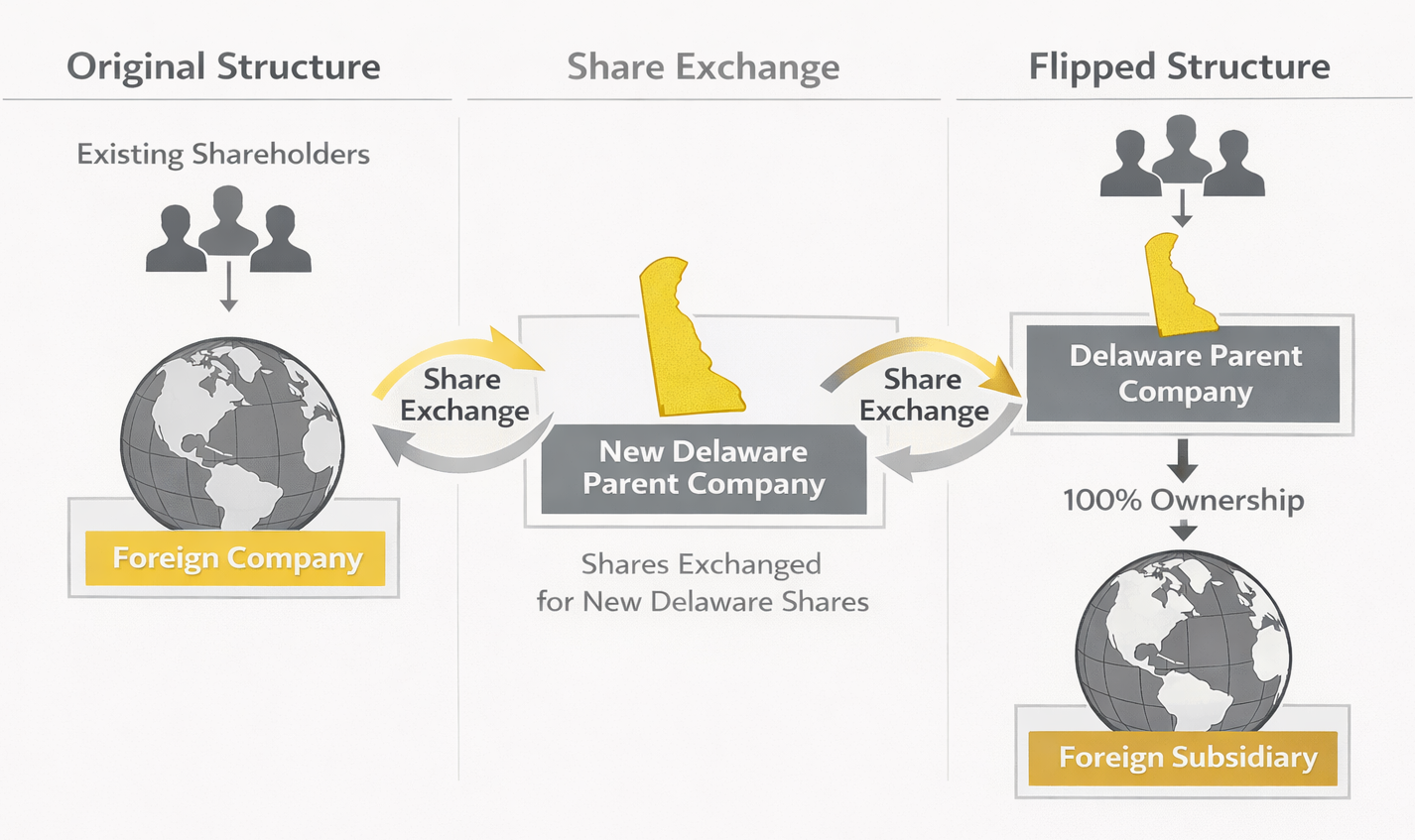

For many non-U.S. startups, the solution is a “Delaware flip.” A Delaware flip is a cross-border corporate reorganization in which a newly formed Delaware corporation becomes the parent of the existing non-U.S. operating company. While the structure is common and often expected by U.S. investors, it is rarely simple. A flip touches corporate governance, securities law, tax, employee equity, and local law requirements, and missteps can be expensive or irreversible.

This post walks through what a Delaware flip actually involves, why U.S. investors often require it, and where complexity tends to arise in practice. We also cover timing considerations, key tax and compliance issues founders should understand, and what comes next once the restructuring is complete.

Understanding the Delaware Flip

A flip usually follows the following sequence: a new Delaware parent company is created, existing shareholders exchange their shares in the foreign company for equivalent shares in the Delaware entity, and the original company continues as a wholly-owned subsidiary beneath the new corporate structure.

When start-ups reincorporate in the United States, they most commonly opt for Delaware, the standard state of incorporation for U.S. VC-backed companies. Delaware offers a mature (and therefore typically viewed as more predictable) body of corporate law, a specialized Court of Chancery with deep expertise in business disputes, and widespread familiarity among U.S. investors and their counsel. For venture capitalists deploying capital across dozens of portfolio companies, this standardization matters enormously.

Assembling the Right Team

Executing a flip requires coordinated expertise across multiple jurisdictions and disciplines. U.S. corporate counsel handles the Delaware formation, US securities law compliance, and preparation of new corporate governance documents. Local counsel in the original jurisdiction navigates the subsidiary conversion requirements, which vary significantly by country. U.S. tax advisors structure the transaction to minimize tax leakage and ensure compliance with complex rules governing cross-border reorganizations. Local tax advisors address exit taxation, withholding obligations, and any other tax considerations in the original jurisdiction.

Beyond professional advisors, a successful flip requires careful coordination with existing shareholders and other equity holders. Because all or nearly all equity holders must participate, early and clear communication is critical to maintaining alignment and avoiding delays.

What Drives Complexity

Not all flips are created equal. Several factors determine whether a restructuring is relatively straightforward or demands months of intensive work.

The size and structure of the cap table are among the most significant drivers. A company with three co-founders and no other shareholders presents relatively minimal coordination challenges. A company with twenty investors, each holding preferred shares with specific rights, requires more extensive documentation to preserve those rights in the new structure.

Outstanding equity instruments multiply the work. Stock options are typically replaced with new grants under the new Delaware entity’s equity incentive plan, which can trigger analysis of potential tax and accounting consequences. Convertible instruments like SAFEs, convertible notes, and warrants are typically assigned or assumed by the new Delaware parent and converted into the right to receive the new parent company’s equity rather than the now-subsidiary foreign entity.

Existing institutional investors can add layers of approval requirements. Their consent is usually necessary, and their counsel will typically scrutinize the transaction to ensure preference stacks, liquidation rights, and protective provisions carry forward in a substantive way, without dilution or impairment.

Local law requirements vary dramatically and can prolong the timeline. Some jurisdictions require shareholder meetings with extended notice periods, regulatory approvals, or mandatory disclosures. Others permit streamlined processes for small private companies. This variability makes early engagement with local counsel critical.

Timing the Flip: Earlier vs. Later

Timing is among the most consequential strategic decisions in planning a flip. As a general rule, earlier is usually simpler. A company with three founders, no investors, and a handful of employees may be able to complete a flip in weeks with manageable legal costs. The same company with fifty shareholders, two prior funding rounds, and dozens of option holders could require months of work and substantially higher expense.

Earlier flips also minimize tax cost basis issues. When shareholders exchange their foreign company shares for Delaware parent shares, the transaction can trigger taxable gain, depending on the structure and applicable tax rules. As a result, lower valuations at earlier stages help to reduce potential tax liability.

Despite these advantages, many founders delay flips until U.S. investor commitment is confirmed. Flipping speculatively, before knowing whether U.S. fundraising will materialize, imposes costs and complexity that may prove unnecessary. A common middle ground is executing the flip immediately before or concurrent with a U.S. venture financing, when investor demand for Delaware incorporation is certain and deal momentum can absorb the additional workstream.

Critical Tax and Compliance Considerations

Tax planning is central to flip execution. U.S. tax law treats cross-border reorganizations with scrutiny, and missteps can result in unexpected tax liability for the company or its shareholders.

A key question is whether the transaction can be structured so that existing shareholders do not recognize taxable gain on the exchange of their foreign shares for U.S. parent company stock. Achieving that result depends, among other things, on the form of the reorganization, the continuity of ownership before and after the flip, the treatment of any cash or other non-stock consideration, and compliance with applicable U.S. tax and reporting requirements. Because these factors are highly fact-specific, careful upfront structuring and coordination with tax advisors is critical.

Section 83(b) elections also deserve attention. Founders often receive stock in the new Delaware parent subject to vesting, a common arrangement to align incentives or satisfy investor requirements. The IRS treats that stock as compensation property under Section 83 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Without a timely 83(b) election filed within thirty days of the flip, founders who are or later become U.S. taxpayers while the shares vest face ordinary income tax on the stock's appreciation as it vests, potentially at significantly higher valuations. The election allows founders to pay tax on the initial (often nominal) value and treat future appreciation as capital gain. Missing the thirty-day deadline is irrevocable. Foreign founders should seriously consider filing preemptively if there is even a small possibility of becoming subject to U.S. tax while the stock is vesting.

Beyond federal tax, founders must address state and local tax registration, potential franchise taxes, and ongoing compliance obligations in Delaware and any states where the company maintains operations or employees.

U.S. Investors Drive the Flip

The Delaware flip is rarely a founder-initiated priority. It typically emerges as a requirement or strong preference from U.S. investors during fundraising negotiations.

U.S. investors tend to favor Delaware for familiarity and efficiency. Their legal counsel has deep experience with Delaware corporate governance, fiduciary duty standards, and the mechanics of preferred stock rights. Standardized documentation, drawing on widely adopted form agreements from the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) and other sources, reduces negotiation time and legal costs. Due diligence proceeds more quickly when investors and their counsel are working within a known legal framework.

Delaware incorporation also smooths future exit paths, as acquirers and underwriters in M&A transactions and IPOs often expect Delaware entities. Converting at exit is possible but introduces delays and complexity at potentially the worst possible moment.

Post-Flip: What Comes Next

Completing a flip is not the finish line. The new Delaware parent company must establish its operational and compliance infrastructure in the United States, a process that introduces its own checklist of requirements. For example:

The Delaware parent must generally qualify to do business in any state where it maintains a physical presence, employs workers, or conducts substantial business activity. Each state imposes its own registration requirements, fees, and ongoing compliance obligations.

Federal tax setup requires obtaining an Employer Identification Number (EIN) for the new parent entity and establishing proper tax reporting structures for the parent-subsidiary relationship. Even if the company previously operated through a U.S. subsidiary, the corporate restructuring typically necessitates updates to tax registrations and elections.

For companies with U.S. employees, payroll and benefits systems need to be established or transitioned. This includes setting up U.S. payroll processing, withholding and remitting employment taxes, implementing benefits programs, and potentially establishing retirement plans like 401(k)s that meet U.S. regulatory requirements.

Intercompany agreements become critical in multi-entity structures. The Delaware parent and foreign subsidiary typically need intellectual property licensing agreements to clarify ownership and usage rights, cost-sharing arrangements to allocate expenses appropriately, and transfer pricing documentation to satisfy tax authorities in both jurisdictions that intercompany transactions occur at arm's length.

When the non-U.S. company already operated a U.S. subsidiary before the flip, additional corporate restructuring may be necessary. Founders and their advisors must determine whether that pre-existing U.S. entity should merge into the new Delaware parent, continue as a sister subsidiary under the parent, or maintain its existing structure. The optimal approach depends on business operations, tax considerations, and contractual obligations tied to the original U.S. entity.

Practical Takeaways

Founders considering or facing a Delaware flip should prioritize early planning. Once U.S. fundraising becomes a realistic path, begin conversations with experienced cross-border counsel and tax advisors. Rushing a flip to meet a financing deadline can compress timelines, increase errors, and escalate costs.

Budget appropriately for both the flip itself and post-flip implementation. Flip costs vary widely based on cap table complexity, which jurisdictions are involved, and the number and types of outstanding equity instruments. Post-flip setup costs, from state registrations to intercompany agreements, add to the total investment required.

Communication with stakeholders is critical in the flip process. Investors, option holders, and employees need to understand the process, timing, and implications for their equity. Surprises often result in resistance and delay.

Also critical: do not miss deadlines, particularly for 83(b) elections and tax filings. These are unforgiving, and the consequences of missing them can be severe.

Build a post-flip implementation plan before the restructuring closes. Identifying required state registrations, intercompany agreements, and operational transitions in advance prevents scrambling after the fact and ensures the company can operate compliantly from day one under the new structure.